Sorairo Utility is Kengo Saito’s passion project through and through—not only as its original author and all-encompassing lead creative within the production team, but also in how it embodies his whole career, influences, hobbies, and the honest desire for people to chase their dreams without self-doubt.

To talk about Sorairo Utility is to talk about Kengo Saito. His name brings the works of studio Trigger to mind for most people, and while that relationship is indispensable to understanding him as an artist, the separation between him and the company is equally important to grasp. It is, after all, related to the way a project like this came to life.

While Saito’s official profiles always point out that his gateway into the industry was Studio DEEN and BONES, it’s important to consider why he sought that path in the first place. His decision to pursue animation came down to the works he watched growing up, and among them all, the first one he brought up as life-changing in his series of Febri interviews was Diebuster. The show impacted him to the point of seeing himself in its protagonist Nono, boarding a train to go to the big city for an adventure just like he’d gone to a vocational school in Tokyo. Given that influence, he of course tried to join Gainax immediately afterward—which led to just as quick of a rejection, hence his work with the aforementioned companies.

It didn’t take long for those aspirations to turn sour. Barely a year or two later, he found himself having essentially given up on those anime dreams. He’d even moved on to half-time working at a post office, but then he was scouted by a producer who would change his career… and in the process, bring him much closer to the creative team that he was such a fan of. Ryousuke Inagaki had worked all over, from the likes of Square Enix to studio Khara. His link to the Gainax lineage included Trigger as well, with whom he was connected through the Ultra Super Pictures conglomerate; in particular, through the Purple Cow Studios Japan crew that modern sci-fi icon Yasuhiro Yoshiura was close with. It was precisely for a project directed by him, the Anime Mirai 2014 short by the name of Harmonie, that Inagaki recruited Saito as one of the young animators to be trained. Incidentally, another interesting relationship with that project as the nexus was Asari Ai becoming a disciple of animation director Atsushi Ikariya. Nowadays, the two are nearly inseparable figures.

Despite Harmonie being specifically geared toward mentorship, Saito points to Kill la Kill—which Inagaki also brought him to at the time—as the pivotal project in his career. Speaking to CSP, Saito stated that it effectively changed the way he approached work and drawing altogether. He went into more detail in the next entry in his Febri series, where he explained that the way that the likes of Hiroyuki Imaishi operate by the rule of cool made him rethink how he approaches the conceptualization process.

Although he’s always mindful of the collective nature of producing commercial animation (and hence the need to fit within the vision of the director and supervisors), this made Saito pursue the type of drawing that he personally found the coolest. At the same time, however, experiencing Trigger’s culture and their tendency to clash with the limits of the schedule also reinforced his understanding of his own personality; which is to say, someone more measured and willing to adapt to the scope of each project. That’s another quality that to this day is appreciable in Saito’s output, and one line he distinctly drew between himself and this group of creators he admires. I believe that it’s no coincidence that his larger collaborations with the studio have happened across a project led by a more methodical director who has always been able to maintain a healthier schedule than is the norm over there.

That position of adjacency, profound admiration, but not quite complete overlap with Trigger’s nature made Saito a perfect fit for the small company Inagaki was about to found: Albacrow, a creative circle we’ve written about multiple times before. Just like Saito, it included other artists people tend to link to Trigger (like Kiznaiver and G-Witch series directorSeries Director: (監督, kantoku): The person in charge of the entire production, both as a creative decision-maker and final supervisor. They outrank the rest of the staff and ultimately have the last word. Series with different levels of directors do exist however – Chief Director, Assistant Director, Series Episode Director, all sorts of non-standard roles. The hierarchy in those instances is a case by case scenario. Hiroshi Kobayashi and the bold Geso Ikuo) who were technically part of this like-minded circle as they continued to collaborate with their friends over at the renowned studio.

As we’ve also covered before, that Albacrow group got later incorporated into Yostar Pictures when the parent company felt the need to create a studio. While that changed their scope and the type of projects they’re able to tackle—look no further than Aninabe’s ongoing work for Arknights—things remained the same as ever in other regards. That change happened in between the production of Gridman and Dynazenon, yet the team produced an episode in each all the same, with Saito himself remaining as one of director Akira Amemiya’s most trustworthy supervisors.

It was during that period that Saito developed an interest in golf, as well as a desire to one day create an anime with that as its theme. He would often proclaim so on Twitter, gradually developing the designs of specific characters that should be recognizable by now. While pitches usually take more calculated approaches, Amemiya reminisced about the spontaneous and creator-driven way that Sorairo Utility came to life in another Febri interview; as it turns out, sometimes being very enthusiastic about your OCs is enough. Besides witnessing its inception, Amemiya noted that he offered his help in whichever area Saito needed him as payback for all that previous assistance. That turned out to be the storyboarding process, as Saito admitted to struggling to create visuals from scratch. Given the responsibility that Amemiya was entrusted with, his general role as a mentor for Saito, and the latter’s newfound appreciation of careful tempo and pauses (acquired through Susumu Mitsunaka’s Haikyuu), it comes as no surprise that Sorairo Utility has always had a flavor reminiscent of Gridman.

It was during that period that Saito developed an interest in golf, as well as a desire to one day create an anime with that as its theme. He would often proclaim so on Twitter, gradually developing the designs of specific characters that should be recognizable by now. While pitches usually take more calculated approaches, Amemiya reminisced about the spontaneous and creator-driven way that Sorairo Utility came to life in another Febri interview; as it turns out, sometimes being very enthusiastic about your OCs is enough. Besides witnessing its inception, Amemiya noted that he offered his help in whichever area Saito needed him as payback for all that previous assistance. That turned out to be the storyboarding process, as Saito admitted to struggling to create visuals from scratch. Given the responsibility that Amemiya was entrusted with, his general role as a mentor for Saito, and the latter’s newfound appreciation of careful tempo and pauses (acquired through Susumu Mitsunaka’s Haikyuu), it comes as no surprise that Sorairo Utility has always had a flavor reminiscent of Gridman.

While the 2021 short film served as proof of concept for that laid-back approach, it’s the 2025 TV show that has allowed Saito to make a statement. The person who rallied for his original characters and personal hobby to be animated has remained at the core of the production to an unusual degree; Saito storyboarded a large part of the show, acted as the chief animation directorChief Animation Director (総作画監督, Sou Sakuga Kantoku): Often an overall credit that tends to be in the hands of the character designer, though as of late messy projects with multiple Chief ADs have increased in number; moreso than the regular animation directors, their job is to ensure the characters look like they’re supposed to. Consistency is their goal, which they will enforce as much as they want (and can). for his own cast all the way through, and went out of his way to handle the opening and ending as well. The latter sequence in particular is a beautiful distillation of the show’s entire worldview. Saito overlays his own illustrations on top of photos yet deliberately retains artifacts, emulating amateur mistakes like being out of focus, to make it appear like youthful collages by the girls themselves. It’s not that perfect blending wasn’t needed, but rather than this convincingly rougher presentation gets Sorairo Utility’s wish across more clearly—and that’s for people to find something they’re passionate about, without fears about whether they’re doing it right or not.

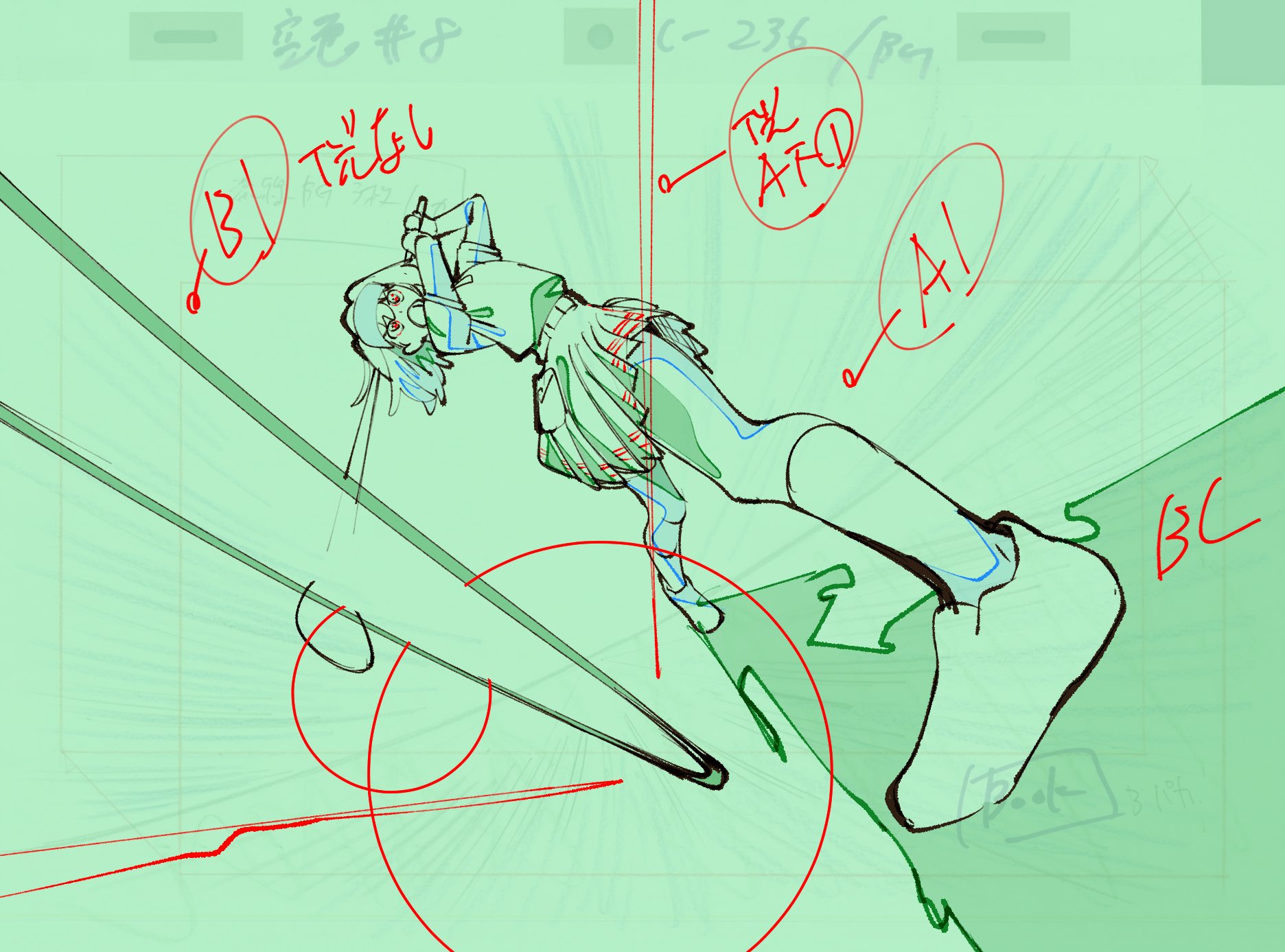

To convey that message, the narrative follows Minami Aoba: an entertaining goofball on the surface, but also someone who embodies the human fear that others are leading brighter and more fulfilling lives. While her own arc would have been enough to tackle that internalized self-deprecation (especially given the occasionally brilliant storyboarding that illustrates it), Saito’s team makes a point to express how everyone can fall prey to those feelings. Ayaka Hoshimi, established as a popular influencer in the TV show, showcases a fear that her relationship with this hobby may be more superficial than her friends’ as she performs it to an audience. This imposter syndrome is best exemplified in another excellent board, corresponding to Masaoki Nakajima’s avan for episode #09. The way that it’s specifically her face—the side of her she sells to the viewers—that is ingeniously obscured in every shot while her friend is plainly visible as she engages honestly with golf captures those fears. And yet, it’s the seeds planted there that build up to an equally impactful realization that her actions were reaching real people out there, validating her own path.

In the end, all arcs come down to this idea that there’s no such thing as following your dreams the wrong way as long as you find fulfillment in the process; which, more often than not, is achieved precisely by dropping those fears. Saito was able to do that much, in an industry he’d quit once but found the will to rejoin, and in new positions he initially felt unqualified for. To simply summarize the result as an introspective work, though, would be a big misrepresentation of what Sorairo Utility also is: a chirpy, funny comedy that draws from the career we’ve been detailing. This is to say that, for every moment where it tackles the unhealthiness of solely results-oriented views or the sometimes isolating nature of talent, there are a handful of goofy gags that make use of the cartoonier tendencies of the animation.

The show’s expression work, posing and timing, and even the eyecatches you can see above draw from Gainax and Trigger lineage through Amemiya and Saito himself. The golfing parts, which are usually attached to the more atmospheric delivery, are also quick to embrace specific stylizations reminiscent of classic mecha anime and the titles that are directly inspired by them. If these were isolated instances, the swerves might feel odd, but the consistent cohabitation between these separate modes gets you used to a duality of tones. It’s even the type of project where you can tell a fair number of people even had fun around the show. Sometimes, the team goes out of its way in spectacular fashion to commission an original song from the performer of Dragon Ball‘s legendary first opening, just because the episode features old side characters with nostalgic, anime-inspired (wannabe) finishing moves. It doesn’t matter that the specifics will fly over the heads of all viewers who don’t check the credits—someone clearly thought this would be a hilarious idea and they acted upon it, just like they decided to publish a deliberately irritating game born from the show.

This wilder side of the project and the more boisterous side of the production that is often associated with it thickens the flavor of Sorairo Utility, but in the end, Saito remains himself. In retrospect, it’s hard not to think about that realization he reached when witnessing the chaos during KLK: that he’s very attracted to the bold, self-centered personalities behind such works, but that he himself is not the type of creator who thrives in clashing with the schedule and resources. It’s not as if Saito refuses to work hard—the sheer amount of roles he undertook speak for themselves—but he seems quite good at finding the natural walls of a project and working within them. Sorairo Utility isn’t the most ambitious project you’ll come across, but it always feels like it’s using every opportunity to deploy amusing animation and nuggets of superlative direction to get its charm across.

We don’t even have to guess about whether the individual at the core of this series listened to his own message about enjoying your passions without being swallowed by self-doubt about what you might be able to do better—he’s happily begging for an opportunity to animate a sequel for it. Given that he tweeted his way into this project’s whole existence, perhaps he’ll be rewarded one day. In the meantime, both the original pilot and this TV series are a solid recommendation for anyone who wants to relax (and sometimes tense up with its sharp stabs at your psyche) while watching a good cartoon. And if you’re in the mood for even more pleasant, efficiently-made anime, we may have just published another piece you ought to check out.

Support us on Patreon to help us reach our new goal to sustain the animation archive at Sakugabooru, SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites’ brand. Video on Youtube, as well as this SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites’ brand. Blog. Thanks to everyone who’s helped out so far!

Become a Patron!